In the early 1970s, as an underage teenager, I snuck into a San Francisco bar where Hot Tuna, featuring two members of the psychedelic rock group Jefferson Airplane, was playing traditional acoustic blues music.

In the crowded, smoky bar I was sitting next to what I considered to be a real old guy, probably at least 40 years of age, who had a fake diamond stud earring and a walking stick at his side. When the group performed a song called “San Francisco Bay Blues” I told the old guy that they must had written that song themselves.

“No, man, that tune was written by Lone Cat Fuller,” he said, puffing on his Pall Mall. “He’s an old black dude from the South; plays at some barbeque joint over on Haight Street.”

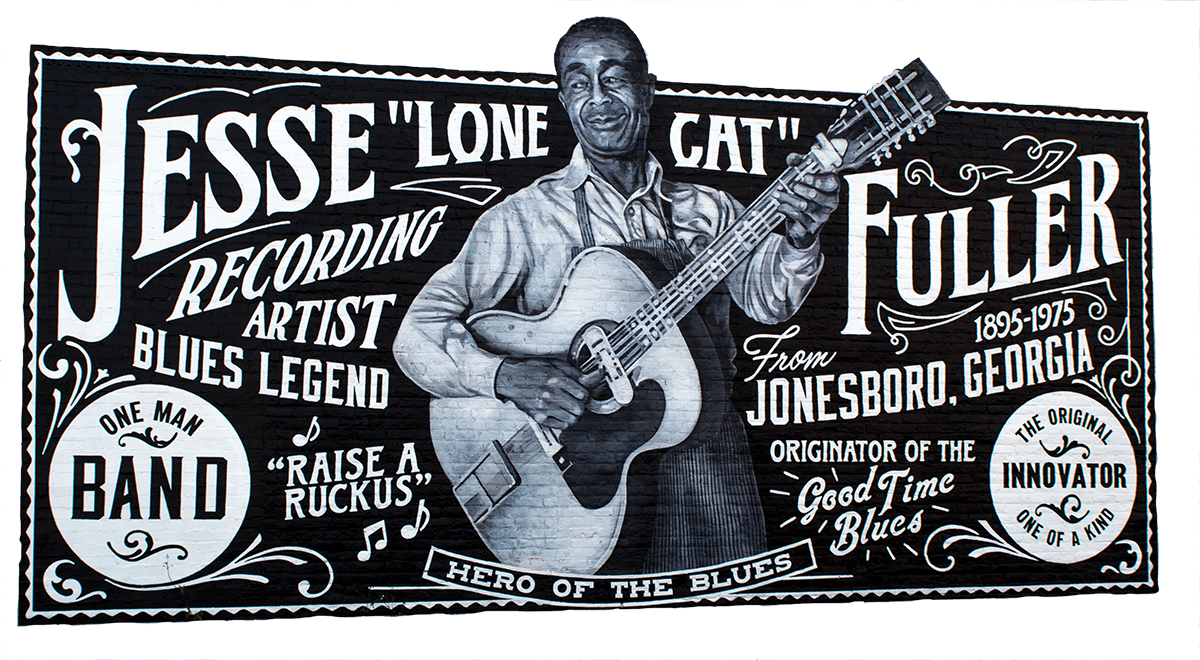

That bit of information got lost in the fuzziness of the following decades until I spied a huge mural on a downtown Jonesboro building. Jesse “Lone Cat” Fuller, from Jonesboro, Georgia, it declared. Dressed in bib overalls and picking a 12-string guitar, Jesse Fuller has a sly smile and a discernable twinkle in his eyes. He is a Hero of the Blues the mural, part of the #jonesboropublicart project, proclaims, along with saying he is a one-man band and a blues legend.

The blues has always touched my soul. Famed bluesman Brownie McGhee said it best: “I never had the blues, the blues had me.” There is just something about singing songs about poverty, lost love, bad times, and misery with humor and dignity that transcends the subject matter, lifting the listener up from the mire into a softer, gentler place. It eases whatever blues you carry on your own, at least for the moment.

So, who was this man on the mural, this blues legend, and what was he doing in Jonesboro?

Jesse Fuller was born in Jonesboro in 1895 to a missing dad and an indifferent mom who gave him away when he was seven years old. He was mistreated by his adopted family and found solace in creating his own mouth harp and guitar by the time he was 10. He ran away after graduating the third grade and drifted across Georgia and Alabama, working mostly in manual labor jobs: laying down railroad tracks, sweating in a lumber factory, working as a canvas stretcher in a circus, building chairs.

He left the South for Cincinnati where he spent time running a streetcar. He moved on to California when he turned 24 and took to the streets hawking his handmade wooden snakes. Later he found work shining shoes outside the studios at United Artist where he befriended one of the silent screen’s biggest stars, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr, who gave him work as an extra in such epics as “The Thief of Bagdad” and “East of Suez.” Fairbanks even bankrolled Jesse’s opening a hot dog stand at his old shoe shine corner. With the money from the stand Jesse moved to Oakland, where he toiled on the Southern Pacific Railroad.

All those years he would make a few extra coins by singing on street corners doing show tunes, gospel songs, ragtime, folk tunes and the blues. But he never thought he could make it professionally until after World War II. The railroad job over, he started another shoe shine business in Berkley. Here in the late 40s and early 50s he drew the attention of bay area folk singers who came to listen as he shined shoes and sang songs he had learned from his years on the road. Soon he was performing at several bay area bars and clubs. And in 1958, at the tender age of 62, he recorded his first album, released on the Good Time Jazz Records label, featuring such great blues classics as “Stagolee” and “Hesitation Blues.”

He said he could never find good enough musicians to play with, although some say he didn’t want to pay others to play with him, so he invented the fotdella, a six-string bass he played with one foot while the other foot beat out the rhythm on a high-hat cymbal. He invented a rack to hold a harmonica and kazoo. This amazing man would simultaneously play a guitar while bumping the bass, hitting the cymbal, and either singing or playing the harmonica.

It is believed that Bob Dylan got the idea for his harmonica rack and his early gravelly voice from listening to Jesse Fuller. Indeed, Dylan recorded a Fuller song, “You’re No Good,” for his first album. Check out Fuller’s harmonica rack and fotdella in a black-and-white recording of “San Francisco Bay Blues” on Youtube. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uBME_J0pf3o)

In his rendition of “San Francisco Bay Blues” there is a line “I ain’t got a nickel and I ain’t got a lousy dime” that is sung with such energy and liveliness that you forget Fuller is totally destitute, just had “the best girl I ever had” leave him, and only wants to lay down and die. Many others – including the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, and Jim Croce – have recorded the song without filling it with the dynamism that Fuller creates.

In 1959, while returning from a day’s labor of picking walnuts, Fuller learned he had been booked into a European tour, playing dates in England, Sweden, Denmark and West Germany. Fuller’s music was grabbed onto by early rock and roll groups such as The Rolling Stones and The Animals, two early 60s bands who stole the Blues and made it a brand-new sound that came back to America as “the British Invasion.”

Peter, Paul and Mary had a monster hit with their folk version of “San Francisco Bay Blues” as did many other folk and rock groups. Jesse Fuller took it all in stride, however, playing coffee houses and small clubs along with huge festivals like the Newport Folk Festival and the Monterey Jazz Festival over the next few years. In 1966, he performed with The Rolling Stones twice while on the road in England, but he always returned to his humble Oakland home where he and his wife raised three daughters. He died in 1976 and is resting in his adopted hometown where musicians come frequently to leave guitar picks, beer bottles and flowers.

The Smithsonian Institution has in its vast collection Fuller’s fotdella and 1962 Sears & Roebuck Silvertone guitar. Yet it is his music that will always be remembered. It can still fill a room and get your foot tapping and your fingers snapping. The blues ain’t about feeling bad; it’s about healing what ails you.

Jonesboro finally decided to honor its hometown legend with the mural. City Manager Ricky Clark, Jr., told me when the project started they just Googled “Jonesboro music” and up popped Jesse Fuller. Artist Shannon Lake was given the task of bringing Jesse Fuller back home with the image, taken from the album cover of Frisco Blues, a record released in 2009 on Arhoolie Records. The mural and the one of Scarlett O’Hara opposite Jesse’s are the foundation for what Clark envisions becoming an Arts and Entertainment district in downtown Jonesboro.

Then Clark said something interesting. “We’re asking people to take a selfie in front of the mural and post it to #jonesboropublicart.”

A selfie in front of a lone cat! It’s been a long time coming for Lone Cat Fuller to be honored by his hometown, and if he were still alive I’m certain Jesse Fuller would be writing a rocking tune called “The Selfie Blues.”