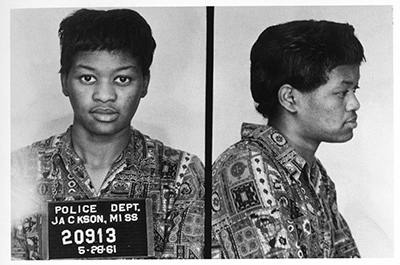

Freedom Rider, Dr. Pauline Knight-Ofosu, Rhode a Bus Into American History

“I used to say we were called; then I said we were chosen; and now I honestly think we were ordered .”

Pauline Knight-Ofosu remembers her decision 50 years ago to become a Freedom Rider as an almost mystical event, one in which her decision to ride into the jaws of the segregated South was determined by a higher power. All she knew was it was the right thing to do. She, along with hundreds of other Americans, both black and white, were challenging the segregation laws that had supposedly been wiped away by several Supreme Court decisions stretching back to the 1940’s.

Today, living quietly as a retired Environmental Protection Agency official in her small, neat home in a nondescript Clayton County subdivision, Knight-Ofosu remembers growing up in Nashville, Tennessee, as one of 11 brothers and sisters who were denied their basic rights as American citizens. The day this became clear to her is burned into her mind as being a hot September day in 1955 while she attended Washington Junior High School. It was the day that the murders of Emmett Till were aquitted. Emmett Till, a 14-year old boy, whose beaten, mutilated dead body was discovered in Mississippi’s Tallahatchie River. The murderers were white men who believed that Emmett Till flirted with a white woman. To the horror of America and the world, despite corroborative testimony, they were set free. Jet Magazine published the first detailed story of the Emmett Till murder. Local news reporter’s cameras, however, showed a gleeful back slapping handshaking, blatant celebration of the murder.

“It was so disturbing, so terrible,” she said, the pain of that far distant day still visible on her face. Worried school officials called off classes and had the entire student body assemble in the auditorium to discuss this openly violent crime. “They said you had to be more vigilant. You have to be focused. This was a time to be more alert.”

A few months later, that same fall season, Rosa Parks became the “mother of the freedom movement” by refusing to give up her seat to a white person on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus. The winds of change were blowing in America, and Knight-Ofosu was swept up in the non-violent civil rights movement.

“In my house everybody had their own Bible, my parents were strong Bible students and encouraged us to be as well, you had to study it. At the age of 14 I began a more a structured bible study by enrolling into a correspondence course. I received a certificate dated, September 11, 1955, for completion of the course “I didn’t know I was being prepared to be a Freedom Rider.”

Her parents also stressed a love of the arts. Knight-Ofosu enjoyed going to the movie theaters, concerts, stage plays and various other performances in colleges, churches and museums. But to get into some of the movie theaters in downtown Nashville, Tennessee, she had to go through an alley, buy a ticket at a small window and then walk up several flights of stairs to sit in a balcony. The NAACP put out a bulletin that read, “Alleys are for rats.” So in the late 1950’s and early 60’s she participated in a series of stand-ins where black patrons were not allowed to enter through the main entrance with whites, which eventually integrated the theaters in the city.

During one of the stand-ins, a white man spat on her and was taken aback when she calmly asked him for a handkerchief. In the course of this time Knight-Ofosu was a student at Tennesse State University. She worked on campus and had two other jobs off campus when she learned of courses in non-violence, taught by the Rev. James Lawson and other ministers. They were experts in non-violence training who used Jesus Christ and Ghandi as their models.

The Freedom Riders were organized by the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) to challenge the segregation laws in the Deep South. In May of 1961, blacks and whites got on two interstate bus lines, Greyhound and Trailways, in Washington D.C., to attempt to ride from the nation’s capitol to New Orleans. They were trying to duplicate the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation where 16 activists, who were inspired by the original Freedom Rider Irene Morgan, defied Jim Crow laws. Her refusal in 1944 to give up her bus seat to a white passenger resulted in the Supreme Court’s ruling in Irene Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia, that segregation on interstate travel violated the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

That ruling was largely ignored until 1958 when Bruce Boynton, a black student at Howard University Law School in Washington, D.C., was arrested in Richmond, Virginia, for trying to order food in a racially segregated restaurant during a bus stop. His case also went to the Supreme Court, which in the 1960 case Boynton v. Virginia, further extended the Morgan ruling to make illegal segregation in the bus terminals used in interstate bus service.

The inaugural Freedom Ride was a test of the Boynton v. Virginia decision, but it was stopped when the first Freedom Riders were savagely beaten in Anniston, Alabama, where one of the buses was firebombed, and in Birmingham, where the notorious police chief “Bull” Connor gave the Ku Klux Klan 15 minutes to use bats and metal pipes to attack the riders.

“Students are the freest people to take some kind of action. My parents knew I had participated in Civil Rights activities downtown, but they wanted me to finish my exams, so I did,” she said. After her exams were over she heard a voice telling her what items to pack for the trip. And what clothes she would wear. Items like a cotton shirt waste dress that would not wrinkle or show dirt. Somehow she found a sweater that buttoned up all the way to her neck to wear for the still cool May evenings she would encounter. Once she completed all she had been instructed by The Voice, Knight-Ofosu retired for the evening.

“The following morning, May 28, 1961, my dad and one of my brothers had already left for work. It was my mother and other family members who were sitting eating breakfast when I told them, ‘I won’t be back today. I am a freedom rider and I’m going to Mississippi. My mother just looked straight ahead without a reaction, and no one else in the room said anything either”. Knight-Ofosu said. “This was a God orchestrated event”. Interviewed for the PBS documentary Freedom Riders, Knight-Ofosu said, “It was like a wave or a wind that you didn’t know where it was coming from or where it was going, but you knew you were supposed to be there.”

Like in a scene from The Twilight Zone, Knight-Ofosu said she walked out her front door and was immediately at the bus station. Once there at the station, in line to get on the bus, she was told that she would be the spokesperson for that group and incidentally she was the only woman for that group (7 men and 1 woman) on that bus.

Arriving in Montgomery, Alabama, these Freedom Riders entered the bus station and took seats in the general waiting area rather than sitting in the designated segregated area to wait on the next bus which would take them to Jackson, Mississippi. Upon leaving the Alabama bus station a member of the Alabama National Guard got on the bus and announced that the Alabama National Guard would be escorting them to the Mississippi National Guard designation. “When the Alabama Guard no longer had jurisdiction they got on the bus and told us that they had gone as far as they could but that the Mississippi National Guard would be meeting us a little piece down the road to escort us into Jackson. We rode for a very long period and still no visible awareness of any Mississippi National Guard escorts. It became eerily obvious that we were not being protected”.

Finally, we arrived at the Jackson, Mississippi, bus station and were met by the biggest, meanest-looking, angriest policemen we had ever seen. “Move on”, commanded Captain Ray, Jackson, Mississippi Police Chief. When they did not move on, Captain Ray said with a southern Mississippi drawl, “You are under arrest for breach of the peace,” “I was taken to the Hinds County jail where all our study and training came into play.”

The jailers let white people in off the streets to stare at and taunt us. She and the others kept their spirits high by singing, and she swears that the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi were there at one time. “They rocked that place,” she said.

Soon, however, with the jails filled with what would become a total of 435 Freedom Riders, Knight-Ofosu was transferred to a city jail for a weekend and then returned to Hinds County Jail where she stayed until she was transferred with women Freedom Riders, to Parchman Prison a maximum security facility. With the intention to intimidate and instill fear, the women were packed onto a flat bed truck, in the middle of the night, similar to that which animals are transported in. They were forced to stand the entire drive from Jackson to Parchment, going through Money, Mississippi, the place where Emmett Till was murdered.

In a continued effort to break their spirits, when the women were processed into Parchman they were forced to walk through a very large pool of cockroaches before being photographed and fingerprinted.

The women were imprisoned on death row where the “most cruel and unbelievable things” were perpetrated on the Freedom Riders. Knight-Ofosu’s cell was only 13 footsteps from the gas chamber. The lights were left on 24 hours a day so that the prisoners didn’t know what time it was or what day it was. “Parchment facilities was terrible, however, the food was somewhat improved than that at Hinds County, where the beans were not washed and contained glass, sticks rock and dirt”, recalls Knight-Ofosu. She remembers with distaste that the beans weren’t washed and cleaned before they were served. “It was horrible to eat”, she said.

Two memories are seared into her brain. One was when she stood up on the iron bars of her cell door to look out a window. What she saw was a line of black prisoners shackled together “like in slavery times.” The other bad memory was when a Freedom Rider named Ruby Doris, who suffered from ulcers and diabetes, was dragged barefooted down a concrete hallway to be thrown into a shower and scrubbed with a wire brush.

“Post traumatic syndrome is a given for every Freedom Rider,” she said.

Knight-Ofosu would spend a total of 41 days behind bars for simply trying to exercise her rights as an American citizen. When she was released she thought briefly about joining the voter registration efforts in Mississippi but she never felt as if that particular mission was meant for her. So she returned to Nashville.

“My mother and daddy were so happy to see me. They let me sleep every morning until I woke up. My mother made me everything I like to eat. I ate a lot of banana pudding,” she said.

But her fight for justice was not over. Upon arriving at Tennessee State for fall classes, she was told that she and other Freedom Riders were expelled because they were now felons. Knight-Ofosu had to file a lawsuit against the university to be re-instated. “My parents never asked me not to file the suit even though my daddy worked at the university and his job could have possibly been at stake,” she said. She won the lawsuit and was readmitted in the winter quarter of 1962.

“What we did as Freedom Riders was not only right in our hearts, and not only right for our country, but it was right for other countries. After the Freedom Rides so many people started to work together in different ways,” she said.

As a Freedom Rider she had helped spark the Civil Rights movement that would re-shape America in the 1960’s and beyond. Yet after graduating from Tennessee State she would never again take part in a major Civil Rights demonstration. Knight-Ofosu got her degree in biology, attended a medical technology school, being one of the first two blacks admitted into St. Vincent School of Medical Technology in Indianapolis Indiana, 1962. Later she was hired and worked there for a year. From there she went on to become a hematology coagulations specialist, while concurrently teaching laboratory techniques to sophomore medical students at Howard University in Washington D.C. One of the highlights of her stay was the day she took off to watch the Supreme Court in session. There she watched one of her heroes, Thurgood Marshall, sit on the bench as the first African-American justice, the same man who had won both the Morgan and Boynton cases as a lawyer, cases which would send her on Freedom Rides years later. She never cared for life in D.C., however, and in 1968 she came to Atlanta in search of a job. While selling the Negro Heritage Library she approached Martin Luther King, Sr., who everyone called “Daddy” King.

“I made a statement that I hated something, and he stopped me right there and yelled out to his secretary, ‘Make an appointment for this young lady to come talk with me.’ He said if you hate anything then you need to talk to me about it because hate is a killer. You have to love. Don’t hate anything.”

Soon afterwards, while selling the library to a vet at the VA hospital, Knight-Ofosu decided to go downstairs to the lab to see if there were any jobs open. She was instantly hired and with the assistance of one Emory University dental student was made responsible for all laboratory work required/requested during the three to midnight shift. Vivian Jones, who was one of the African-Americans who integrated the University of Alabama, worked in the human resources offices at the same VA hospital. Knight-Ofosu was later recruited by Vivian Jones who by then had become the Regional Director of the Office of Civil Rights at the Region 4 Environmental Protection Agency. That recruitment led to her being named the first female Pesticide Inspector for the EPA.

Surprisingly, until recently the Freedom Riders were not particularly celebrated for their parts in changing American society. Knight-Ofosu said many of them suffered from depression caused by their experiences. One Freedom Rider was so emotionally scarred and injured during the rides that years later he walked into traffic and was killed. “We weren’t always welcomed with open arms,” she said. In 2008 some healing occurred when Tennessee State gave 14 former Freedom Riders who had been expelled an honorary doctoral degree. “I’m not emotional, I’m thankful,” she said in an interview with a local TV station.

Oprah Winfrey brought the Freedom Riders together for a two-day special celebrating the 50th anniversary of the rides. Knight-Ofosu went and said it was a great experience. “It was uplifting and soothing to talk with other Freedom Riders.” Another celebration was held in Mississippi where she heard a young man tell the Freedom Riders that “We need your wisdom and you need to stop focusing on whether these young men pull up their pants or not. You need to elevate their minds.”

Knight-Ofosu refuses to call herself a hero. “I do think that in responding to this call, this order, that teachers got better jobs, schools got better, and everything changed. But the story is still going on. Injustices are still going on today. Although much has changed, it is not enough.”

Sitting in her living room where she has a plaque that commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Riders, a plaque made from the granite swimming pool where she learned to swim decades ago, Knight-Ofosu reflected on what it means to be a Freedom Rider. “When I was ordered I showed up and did what I had to do. We’re not heroes. It was a faceless thing for those who participated. I often remember the advice I received from a teacher who said there is so much good you can do if you don’t care who gets the credit”.