Reginald Scandrett grew up an angry young man. The youngest of four siblings. He was angry at his father for abandoning his family. Angry that his mother was forced to raise four kids on her own. He was angry because he never had enough food to eat. Angry because he had to wear the same clothes for weeks on end. Angry because he lived in a poverty-ridden neighborhood.

Anger boiled in his blood. Anger led his every action.

“I was always challenging people. I was always fighting,” the newly-elected Sheriff of Henry County said. “I was a bad boy.”

In the South West Atlanta Bankhead neighborhood of his childhood, many kids turned to drugs or crime as the only way out of the destitution and hardships. Young Reginald was on the same path when an unexpected person stepped into his life.

His name was Edward Emory, a music teacher at Scandrett’s elementary school who noted the second graders’ musical talent and got him into the advanced band. Suddenly, the anger that had cursed through his veins began to be replaced by the energy surging into his drums. Emory’s son Sonny, who would later play on many major recordings including Earth, Wind & Fire, the B-52’s famous “Love Shack,” became his brother and mentor.

“It created a calm in my life. If it wasn’t for that I’d be in prison now,” said Scandrett. “This was all different for me because I only knew Bankhead. I began to feel that God was telling me to create a new life.”

Music propelled him forward. When he started at Fredrick Douglass High School its band was regarded as one of the best in the state. No 8th graders had ever been invited to join the group, until Reginald Scandrett arrived. Even though he played the relatively lightweight cymbals, he caught the eye of a flute-playing young woman named Deidree’, who was destined to become his wife.

“Seeing him inspired me,” she said of her first impression of the young Scandrett.

Their relationship started with an exaggeration. He told her he was a year older than he was. But they began talking on band bus trips. On one such trip Deidree remembered having her face slathered in Noxzema, her hair in pink curlers, and wearing some old sweatpants. Her appearance did not curtail his interest in her.

Two years after meeting they were still just good friends. After a bus trip they were waiting for their rides when Reginald mumbled, “What we doin’?” That was to lead to a marriage that is still strong after three decades.

At Douglass, Reginald joined the Junior ROTC (Reserved Officers’ Training Corps) where he rose to become the Battalion Commander over 750 other high school students. As a senior, he had to be talked into entering a contest to determine the best JROTC Commander in the state of Georgia, competing with dozens of other candidates.

“I just had a reluctance to compete in such a competition. I was shocked when I made the top 50 and was invited to Fort Benning,” he said. “I still didn’t think I had a chance. Then I made the top five and thought that was it.”

He was named the Best JROTC Commander in the state for 1987.

Despite having 14 full scholarships to colleges, Scandrett chose to follow his future wife to Clark College, where his partial scholarship left many bills unpaid. Scandrett’s mother was furious over his decision, especially when he quit college after only a year to work as a security guard at The Coca-Cola Company. Although he made extra money by providing home security for some Coke executives, it still wasn’t enough.

“Life happens,” he said with a smile.

An opportunity to join the DeKalb County Sheriff’s Office came along in 1990. A conversation with a former high school band director convinced him to take the offer. The band director told Scandrett his starting salary with the Sheriff’s Office was more than the band director was making after almost 30 years in teaching.

The former bad boy began a 29-year career in law enforcement that was to lead him to promotion after promotion, culminating in becoming the highest ranking non-elected official in the office. He served under seven different sheriffs in his career, rising to become the Chief Deputy Sheriff in DeKalb County from 2014 until his retirement in 2019.

Scandrett as Chief Deputy Sheriff would oversee a budget that grew from around $56 million dollars to some $92 million. He is most proud of the fact that under his leadership the office had a 97 percent rate of solving crimes and bringing the offenders into custody.

The boy from South West Atlanta had an unusual reaction to the criminals locked up in his jail. He knew he could have easily been one of them if not for the intervention of good people in his life. He remembered being so angry as a youngster that it clouded his mind. Perhaps, he thought, “these people are the same as I used to be.”

Scandrett noted that nearly six out of ten people behind bars in DeKalb didn’t have a high school education. He started a GED program in the jail that would eventually see some 1,000 inmates get their diplomas. With the assistance of institutes of higher learning such as Georgia State University and Piedmont College, which helped write grants, Scandrett began a series of Life Skills classes for the inmates, teaching things like landscaping, painting, and construction skills.

“I wanted this to be life altering. I didn’t want them to go back to the things that they were doing,” Scandrett said. “I thought they could become more successful if someone believed in them just like someone believed in me. I believe in the human being.”

His interaction with the inmates caused him to become an advocate of Restorative Justice. In this practice the inmate is introduced to the person their crime most affected. “This is so they can understand the gravity of their actions and what it did to another person,” he said. “Anyone can change. But all we do is create super criminals by just locking them up and throwing away the key.”

While with the DeKalb Sheriff’s office Scandrett juggled his family life, eventually to grow to four kids, with his continuing education, graduating magna cum laude in criminal justice from St. Leo University.

With the sheriff’s office he started a multi-jurisdictional Operation Safe Streets Task Force and the Gang Task Force to confront the growing threat from local gangs. His concern for his fellow peace officers led to the creation of the Metro Atlanta Public Safety Flag Football League. Officers from five metro counties and the city of Atlanta compete in a league that promotes camaraderie while raising money for The Gold Shield Foundation, which assists police, firefighters, and the families of those seriously injured or killed in the line of duty.

A terrible instance in his career led him to immediately institute twice-a-year mandatory psychological evaluations for all his Henry County officers. He had to witness the autopsy of a two-year old girl who had been raped and killed. “That did something to me mentally,” Scandrett said.

Installing the evaluations was one of his first acts as the new sheriff because he believes officers suffer from an undue percentage of divorces, alcoholism, drug usage, and suicide.

“The awful things these officers have to see and deal with causes a slow seepage in their minds. Some of them need to cry and don’t know how,” he said. “Smiling becomes a task.”

When Scandrett retired from the DeKalb Sheriff’s Office he was thinking that perhaps he would want to run for sheriff in his home county of almost 30 years. “I think of myself as a servant, not a politician,” he said. Yet, like when he had to be nudged into running for JROTC Commander of the Year, he hesitated.

Deidree’ told him, “There is a lot more to you.”

Georgia 10th District State Senator Emanuel Jones, who met the future Henry County sheriff while working in DeKalb, told him, “We need you in Henry County.”

As a matter of fact, Jones started talking to Scandrett about running three years before the election. Never mind that an African-American had never been elected as sheriff in Henry County for 200 years, Jones felt the former bad boy was just the strong personality for the job.

“His best quality is that he is a good person that understands the gravity of the moment. Our goal was to tell the voters of Henry County about the man, his record, and his accomplishments,” said Jones. “My only advice to him was not to make the walk alone, that he needed his family and the community.”

He did enlist his wife and children in the campaign. They went to work creating election literature and internet posts, waving signs at intersections, and making sure he made his campaign appearances, mostly on virtual town halls and meetings.

“He’s not a shake-the-hand kind of guy. He’s an action man,” said Deidree’.

Christian, his oldest daughter, was never in doubt of the outcome. “It was a natural next step for him,” she said. “It was meant to happen.”

It didn’t hurt that Scandrett got assistance from a number of well-known personalities who gave their time to his campaign: Andrew Young, Chris Tucker, new Georgia Senator Jon Osoff, and Henry County’s most beloved former athlete and prodigious businessman Shaquille O’Neal, who has become the Sheriff Office’s Community Relations Director.

Outgoing sheriff Keith McBrayer said that Scandrett “had the most qualifications out of the ten candidates.”

His November election highlighted the changing demographics of metropolitan Atlanta. Three African-Americans were voted into their respective county’s office of sheriff, including Craig Owens in Cobb County and Kebo Taylor in Gwinnett.

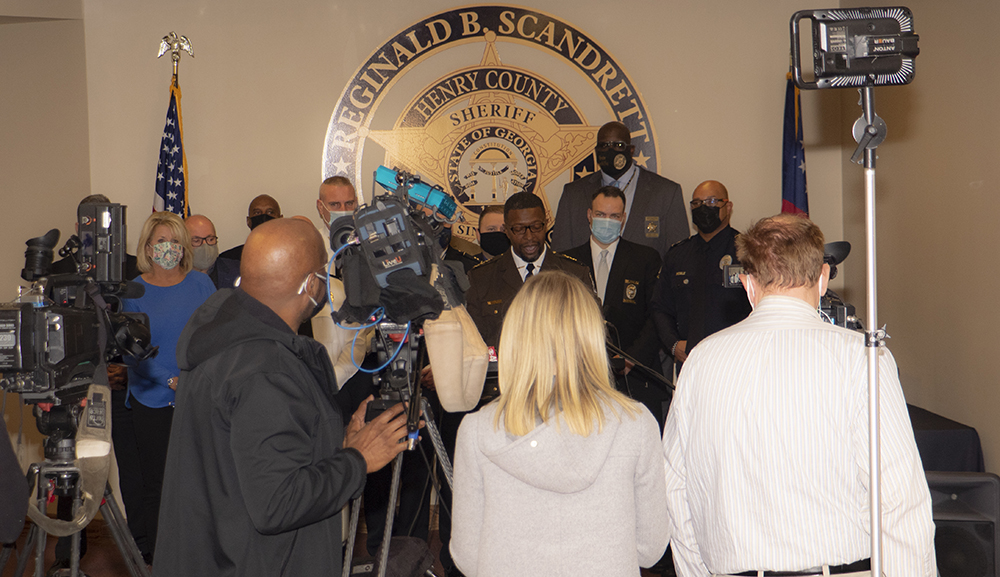

Winning with more than 60 percent of the vote, Scandrett quickly empaneled a group of 16 retired former law enforcement officials to help in his transition to the sheriff’s office. As in his stint in DeKalb, he plans on reducing the rate of recidivism, establishing a system of Restorative Justice, creating multi-jurisdictional collaborations in the metro area, and generally engaging the community despite the inherent differences in the population of Henry County.

“I know there are engrained racial tensions in Henry County, but I can’t wait to sit down with people because differences are what attracts me,” he said. “I just want to plant the seed. I want to talk about life.”

Scandrett has watched the gulf between law enforcement and the community deteriorating over the past few years. He intends to try and heal that divide with the love that has grown in his heart through the years. “The job of a sheriff is to ask people ‘how can I help you suffer less?’ Growing up I suffered a lot of pain and anger because God wanted me to experience the pain,” he said. “But now that anger has turned into a passion. I want to bring people together.”